Processing Olives for Olive Oil and More

Based on the olive oil amphorae discovered, we can safely assume that humans started to process olives for olive oil some time before 4000 BC. Records on olive oil extraction techniques can be traced back to the Roman days. While certain aspects of the process have not changed throughout these years, continuous refinements have led to the three techniques that can be encountered today.

1. The traditional extraction method

As common to all three processes, the traditional method starts with removing the olive tree leaves incidentally collected with the fruits, followed by washing the olives for cleanliness and hygiene.

The next step is crushing the olives to make a paste. This is accomplished using a stone wheel to grind the fruits on a stone surface. It is essential to control this process to not emulsify the oil-water mixture at this stage. Premature emulsification of oil and water here complicates the subsequent steps.

The “kneaded dough” from the crushing step is then spread on scourtin, a knitted, coco-fiber filter. The cleanliness of the scourtin is a critical factor influencing the quality of the oil. Nyons has one of the handful of remaining scourtin manufacturers in the world.

The “kneaded dough” on scourtins are piled on top of each other and form a multi-layer sandwich where the scourtins act like the bread and the olive paste like the meat. This sandwich is then put through the presser as shown below:

Enough pressure is applied to push the fruit liquid, which consists of water and oil, out of the sandwich while the fruit solid, the grignon, remains in between the scourtins. The final separation of the oil and the water is currently accomplished using a disc centrifugal separator.

This traditional method consumes a small amount of additional water, is low in energy consumption, and provides a dry grignon, which can be easily used as burning elements. It is, however, manpower-intensive. Very few mills still operate this process. One of them is in Nyons, where people who live well beyond the local area but are loyal to this method come to process their olives. The oil obtained from this process is thicker and less transparent than that obtained using the other methods. People who stand by this method can perceive the distinctive aroma, taste, and nutritional values associated with the oil produced.

One of the ways to optimize the olive oil yield from the traditional process is to increase the pressure applied to the sandwich so that more of the oil and water is squeezed out. However, even with increased pressure, this technique has reached its limits. In the 1950s, the traditional press was gradually replaced by a decanter known as the horizontal axis centrifugal extractor, marking the start of the continuous processes. In continuous processes, the milling of olive fruits occurs in metallic grinders, which can exert much higher energy than equipment in the traditional process and can thereby enable thorough crushing of the plant cells, which contain oil, water, and other nutrients. This, together with an improved separation mechanism, further increases the availabilities and yields of olive oil, plant water, and other nutrients such as antioxidant polyphenols.

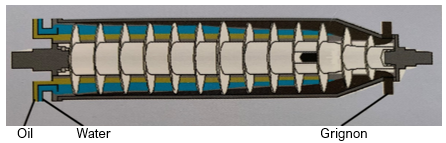

2. Two-phase continuous extraction

In the two-phase extraction process, the decanter is designed to produce two streams—the olive oil from one side and the rest of the material, which is a mix of water and grignon, from the other side. The two-phase process requires a lower amount of additional water compared to the three-phase process. Because water is not separated from the solid materials, grignon from the two-phase process is much more humid than that from the traditional extraction method; it has about 60% water content and appears like a paste.

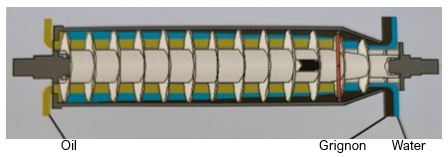

3. Three-phase continuous extraction

In the three-phase extraction process, the decanter is set up in such a way that the oil and water are separated and exit through two separate pipes on one side. The solid phase exits on the opposite side. This process is rendered possible by adding an appropriate amount of additional water to the grinded paste prior to it entering the extractor. With some of the water removed, the grignon produced from this process is drier than that from a two-phase process. The three-phase process allows for the higher throughput rates desired for economic reasons at the expense of using additional water, which creates additional burdens and increases the operation's environmental footprint. Many modern mills are equipped with this process.

At Proscien, we integrate closely with the olive farming and processing communities in Nyons so that we can seek the best possible materials for cosmetic ingredients. Our Prolive™, ProActive™, and ProSenteur™ product lines contain olive ingredients carefully selected with a comprehensive understanding of the local olive ecosystem. Contact us directly to learn more.